America's industrial might — automakers included — determined the outcome of the 20th century’s biggest events. The “Arsenal of Democracy” won World War II, and then the Cold War.

And our factories flew us to the moon.

Apollo was a Cold War program. You can draw a direct line from Nazi V-2 rockets to ICBMs to the Saturn V. The space race was a proxy war — which beats a real war. It was a healthy outlet for technology and testosterone that would otherwise be used for darker purposes. (People protested, and still do, that money for space should go to problems here on Earth, but more likely the military-industrial complex would've just bought more bombs with it.) As long as we and the Soviet Union were launching rockets into space, we were not lobbing them at each other.

JFK’s challenge to “go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard,” put American industry back on a war footing. We were galvanized to beat the Russians, to demonstrate technological dominance. (A lack of similar unifying purpose is why we haven’t been to the moon since, or Mars.) NASA says more than 400,000 Americans, from scientists to seamstresses, toiled on the moon program, working for government or for 20,000 contractors.

Antagonism was diverted into something inspirational.

The Big Three automakers were some of the biggest companies in the moon program, which might surprise a lot of people today. Note to a new generation who marveled when SpaceX launched a Tesla Roadster out into the solar system: Sure, that was neat, but just know that Detroit beat Elon Musk to space by more than half a century.

This high point in human history was brought to you by Ford

It’s hard to imagine in this era of Sony-LG-Samsung, but Ford used to make TVs. And other consumer appliances. Or rather Philco, the radio, TV and transistor pioneer that Ford bought in 1961 — the year Gagarin and Alan Shepard flew in space.

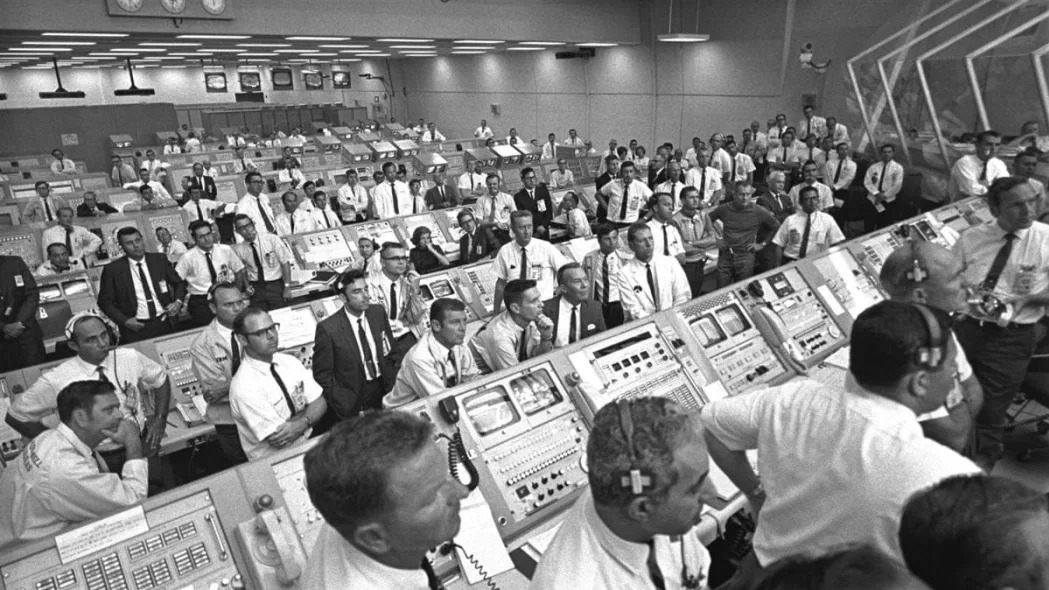

Ted Ryan, Ford’s archives and heritage brand manager, just wrote a Medium article on the central role Philco-Ford played in manned spaceflight. And nothing’s more central than Mission Control in Houston, the famous console-filled room we all know from TV and movies. What we didn't know was, that was Ford. Ford built that.

In 1953, Ryan notes, Philco invented a transistor that was key to the development of (what were then regarded as) high-speed computers, so naturally Philco became a contractor for NASA and the military. In 1963, Philco-Ford became prime contractor to create Mission Control.

As such, Philco-Ford envisioned, invented and built the nerve center of a global space communications and data network when no such thing existed, linking spacecraft, tracking stations and Houston. “A major computer-assisted decision-making capability which no one had when Philco-Ford received the contract,” a company document said.

Ryan shares some fun facts about Mission Control:

- 60,000 miles of wiring were laid.

- 2 million wiring changes had to be made for each new mission.

- 1,500 simultaneous streams of telemetry came down from the rockets, the spacecraft and the astronauts themselves.

- Five IBM computers fed that data to flight controllers’ consoles.

- And Mission Control boasted the world’s largest assembly of television switching gear.

The room oversaw nine Gemini missions, all the Apollo missions, and 21 space shuttle flights.

The Apollo 8 Christmas reading from Genesis in lunar orbit … “the Eagle has landed” and the “giant leap for mankind” ... the Apollo 13 drama that riveted the world … the later missions’ hours of live color TV broadcasts from the lunar surface — we heard and saw all of that courtesy of Ford.

Mission Control is on the National Register of Historic Places, and NASA just completed a restoration/preservation, taking it back to original condition, circa Apollo 15 — right down to the period-correct coffee cups and cigarette butts. Here is how it looks today:

General Motors did all the steering

Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked the equivalent of a mere city block away from the Eagle lander. Apollo 12 and 14 crews trekked further, but NASA needed a way to cover more ground, in bulky spacesuits while lugging hundreds of pounds of geology samples. So here’s the part where an automaker does what automakers do.

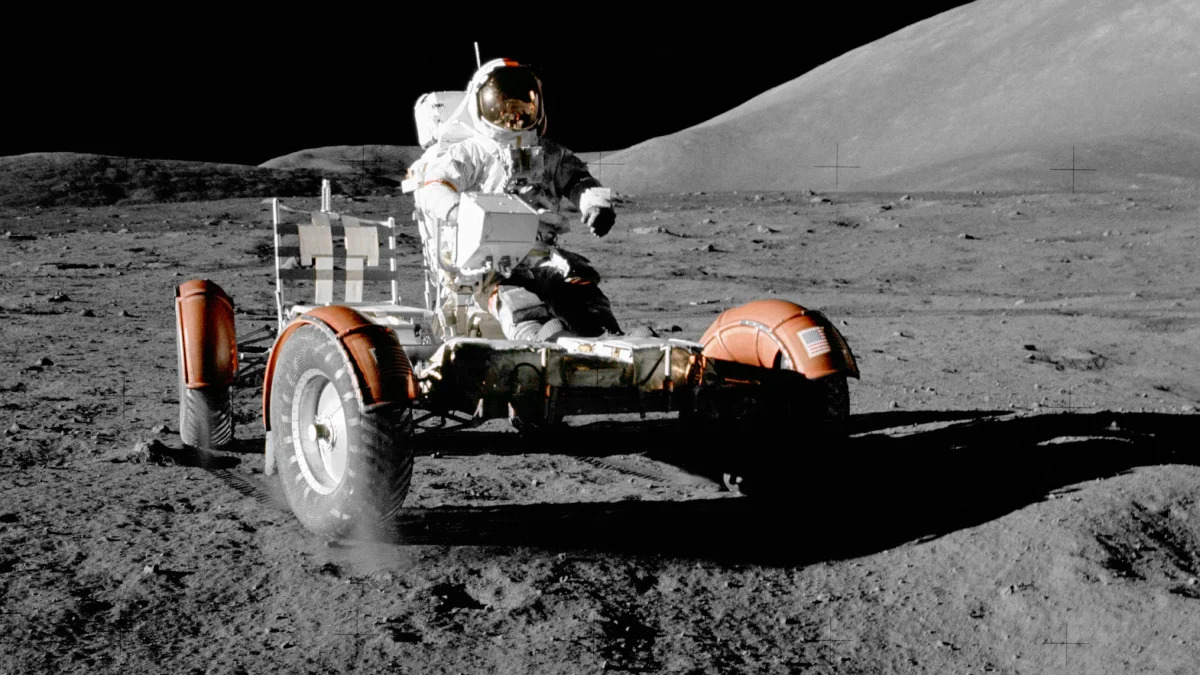

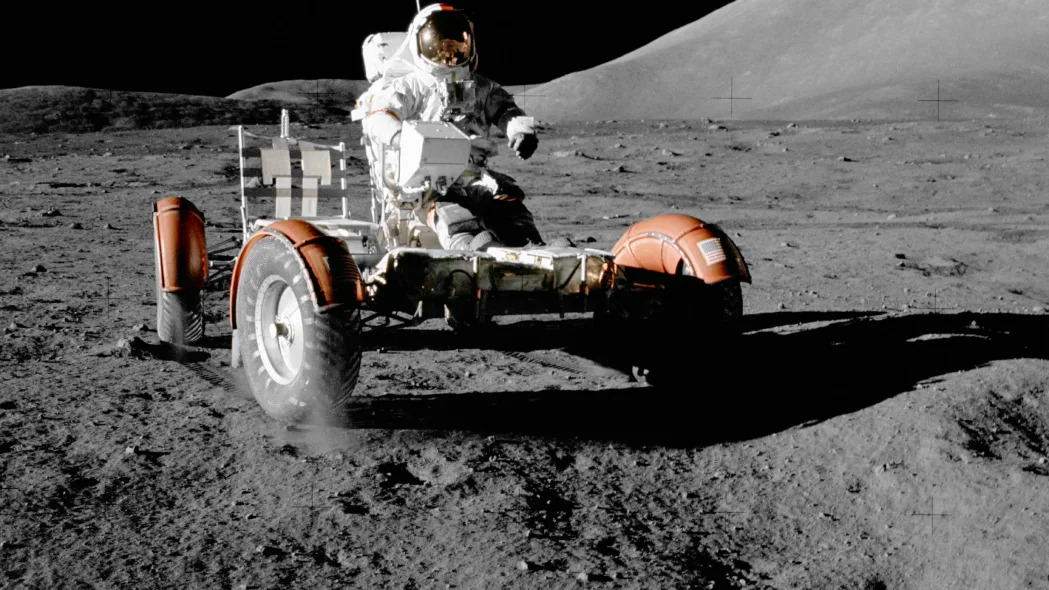

The EV1 wasn’t GM’s first famous electric vehicle — the Lunar Roving Vehicle was. The moon's lack of atmosphere ruled out internal combustion, so GM's Delco, working with prime contractor Boeing, built the LRV, providing its drive components and silver-zinc batteries. (Jon Bereisa, a former GM engineering director, was quoted as saying lessons from the LRV were used in development of the Chevy Volt.)

Modern EVs on Earth can lose range in cold or hot climates, so imagine the challenge of building a battery electric vehicle for a landscape where temperatures can be 250 degrees above — or below — zero. Rubber tires would disintegrate, so the wheels were wire mesh. Meanwhile, the LRV needed to weigh just 460 pounds (on Earth) but carry 1,200 pounds of men and cargo.

The rover flew to the moon folded into a 4-by-4-foot hold in the lunar module descent stage. Astronauts pulled a lanyard to unfurl it to 122 inches long by 81 inches wide. Once on the move, its ground clearance was 14 inches. Its output was a single horsepower, and its top speed was 8.7 mph.

Because testing on Earth was at six times the gravity, no one could be sure how the rover would perform on the moon. They needn't have worried. "By golly, this rover is remarkable," Apollo 15 commander David Scott radioed. "We climbed a pretty steep hill and didn't realize it. This is a super way to travel. It's easy to drive. No problem at all."

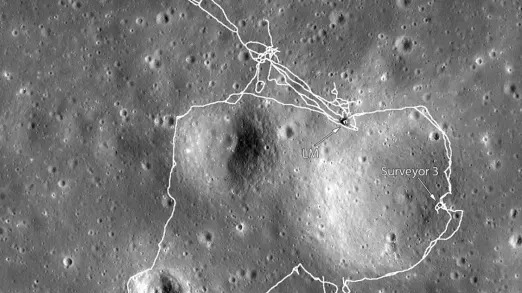

Each of the final three missions spent three days on the lunar surface, so each rover drove three EVAs. Apollo 15 logged more than 17 miles total; Apollo 16’s crew traveled 16.5 miles; and Apollo 17 covered 22 miles. By the last mission, NASA was so confident in the machine that Gene Cernan and Harrison Schmidt ranged nearly 5 miles away from the lunar module. A breakdown would have meant a long walk back. The Apollo 17 rover's route is shown here:

Eight LRVs were built. Three remain on the moon; others were used for training. One’s in the Smithsonian. In the 1990s, Boeing discovered it still had one in storage, so engineers from the project came out of retirement to fix it up. It’s on permanent display in Seattle’s Museum of Flight, currently alongside Apollo 11’s command module, Columbia.

Even more crucial to the moon program, GM developed the spacecraft batteries, along with the Apollo command module and lunar module primary guidance, navigation, and control system (PGNCS). Delco was a military contractor with expertise in aircraft and missile inertial navigation — legend has it, Delco could put a missile through a particular third-floor window of the Kremlin. Luckily that was never put to the test, but we do know that GM’s systems plotted a course to the moon, guided landers to the surface, and brought astronauts a quarter-million miles back home to their families. All using the crude technology of the era.

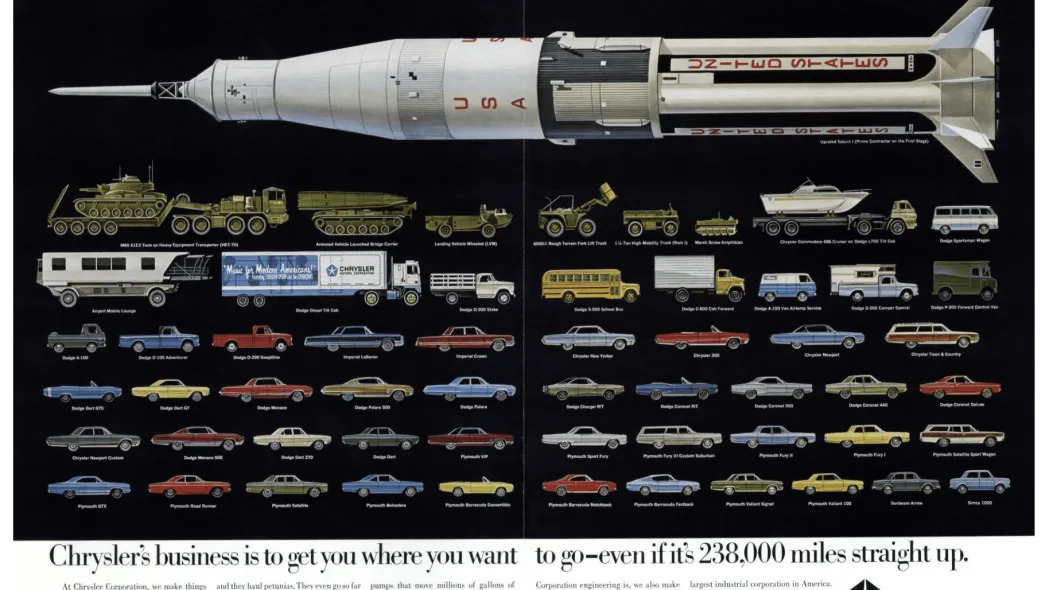

Alan Shepard drove a Chrysler

While GM was guiding rockets, Chrysler was building them. That’s right, the Chrysler that builds minivans today once operated a thriving Detroit-area missile factory, and another near New Orleans.

In the 1950s, Chrysler built the Redstone, a 69-foot-tall ballistic missile meant to carry a nuclear warhead. It was a direct descendant of the Nazi V-2, as both were designed by Werner Von Braun. Chrysler also built other missiles such as the Jupiter and Juno, which launched the first U.S. satellite. But the Redstone, known for its reliability — sort of the rocket version of the Chrysler slant-six engine — was modified into the Mercury-Redstones that carried Alan Shepard and Gus Grissom on their suborbital flights. Yes, Chrysler launched America’s first and second men in space.

If the Redstone was the slant-six, the Saturn rockets were 426 Hemis. Chrysler built the first stage of the Saturn I and IB launch vehicles. The 180-foot-tall Saturn I had a first stage assembled from eight Chrysler Jupiter engines, a “super Jupiter,” and it flew 10 times, including early unmanned Apollo tests.

The next-iteration Saturn IB launched unmanned tests of the Apollo command/service and lunar modules, and it would have launched the astronauts who died in the Apollo 1 capsule fire. In 1968, a Saturn IB sent the crew of Apollo 7 into Earth orbit, and later delivered three crews to the Skylab space station and flew the 1975 Apollo-Soyuz space détente mission.

Chrysler didn’t have a role in the Saturn V moon rocket. But it took important steps that led to the footprint on the moon.

At its peak, Chrysler’s Michigan Ordinance Plant employed nearly 11,000 people, who built hundreds of rockets. Today it’s known as the Sterling Heights Assembly Plant and builds Ram pickups.

Sign in to post

Please sign in to leave a comment.

Continue